You could say that an architect isn’t born, but made—not in the classroom or the studio, but behind a desk at a real design firm, where success and failure affects real clients and happens in real time. For someone starting out, it’s about finding a balance between detailed plans and time constraints, creative vision and technical knowledge, and design and documentation. It’s about understanding the intricate details, knowing what questions to ask, and discovering how a building comes together before the contractor ever sees the plans.

Younger designers learn by working with experienced architects, or “design mentors,” who pass along their knowledge to train next generation of the firm. Over time, they communicate the fundamental design tenets and the practical, technical processes that should guide every project.

But what makes a good design mentor?

Four members of our team—two associate principals and architects (mentors) and two project designers (mentees)—tackle that question head-on.

A good design mentor underscores the value of experience.

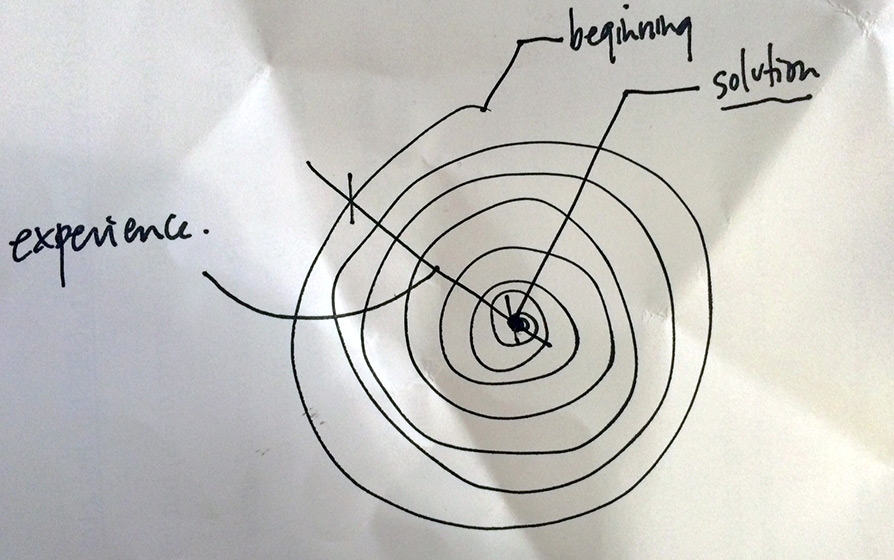

“What’s the definition of a line? You know this—it’s easy. The shortest distance between two points. That’s how we move from problem to solution. When we consider the design process, we tend to see it as ‘volleying,’ and the line looks wavier, but it’s still a line, a way of getting from point A to point B. The reality is that design is a circular process: you start at the beginning, spiral into the solution, and the cross-section between them represents the experience gained on the way there. The value that comes back to the firm is that cross-section – even though we don’t have an easy way of measuring the profitability of experience.” –Alan Davis, Associate Principal | Architect

A good design mentor links the big picture to the little details.

“At Baskervill, we want to make sure that our young architects are not just drafters, or people who are really good at drawing lines, but people who understand the whole process. Ideally, we never just draw lines. When we’re working on a project, every line should be intentional. Our goal is to catch problems ahead of time, so training people who understand that concept is crucial. There’s a real danger to just drawing lines and then pushing them out the door, both figuratively and literally.” –Jay Woodburn, Associate Principal | Architect

A good design mentor emphasizes legibility as a part of great design.

“Mentors allow you to run with things and get to a certain level of completion before they sit down with you and edit what’s wrong. Part of quality control is recognizing that there’s a reciprocity between the digits and the digital. I have learned that sometimes, it’s best to stop clicking, print out the document, and trace over it. Even printing something gives you a fresh perspective on things. You don’t want to stay on the computer until it’s time to send something out.” –Justin Sculthorpe, Project Designer

A good design mentor is hands-on.

“You want to work with someone who is supportive, willing to roll up their sleeves and jump in, who will be in the trenches next to you. They will explain to you why something is wrong in a gracious way. There’s an element of friendship and mutual respect, too—a good design mentor isn’t just an authority figure. They teach you to be better every day, both as an architect and as a person.” –Ashley Nedza, Project Designer

With room to fail safely and time to discover the ramifications of each mouse-click in AutoCAD, young designers learn to evaluate not only the details they’re drawing, but also what those details will touch. Alan compares the process to a funnel.

“You set up parameters so that your mentee doesn’t fall into a ditch. You’re working forward toward a conclusion—teaching them to find a balance between time and detail. How we mentor determines the future of the firm. It affects profitability and liability today and tomorrow.”